Every year the North American Hand Built Show (NAHBS) ignites a buzz around bicycles built with a little extra love, care and attention to detail. Simply put, NAHBS brings a strong awareness to the amount of work that goes into building bicycle frames. Far too often, we look at bike frames as a sum of their parts. But behind the clear coats, trendy colorways, and complex, carbon K weaves lie small details quietly performing their duties, obvious to only the most knowledgeable bike geeks. In reality, no matter what your frame, what its material, it’s these details that give a bike its soul.

Back in 1997 when Seven Cycles was formed, the concept of building a custom, handmade bike on a short timeline without charging a significant, additional fee was revolutionary.

Why? Because a custom frame meant artisan builders had to step outside their normal production process, interrupting their manufacturing flow. They charged fees to cover the extra build-time and lost productivity of that interruption. Seven’s approach was questioned early on when naysayers assumed there wasn’t a way to do ‘custom’ about in the same time others were building stock sizes. Seven’s approach was revolutionary in the bike world, an entire production system designed from the ground up to build custom bikes.

From raw materials to completed frame

So often folks walk into Velosmith and see frames or complete bikes, but they rarely get a chance to see what raw frames look like. In this series, we walk through Seven’s process picking up just after their proprietary coping (mitering) process and follow a steel Resolute frame from a box of tubes to a painted, completed frame.

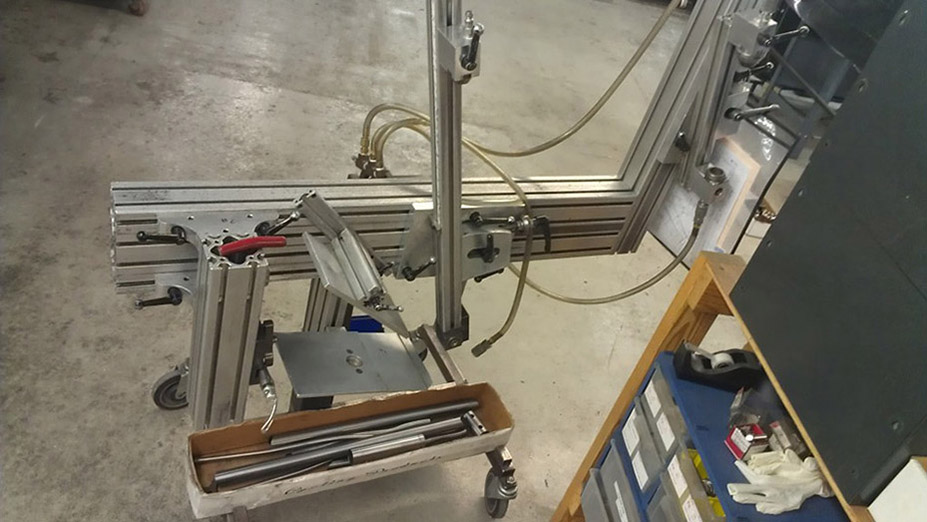

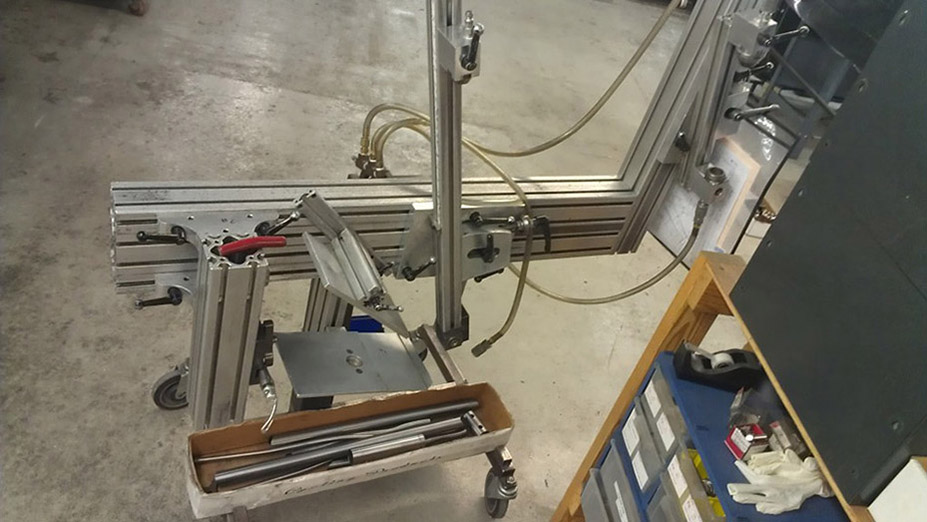

In the photo above, tubing has already been selected based on the rider’s size and riding style. It is cut, mitered (coped) and assembled in the frame jig. At this point, the tubing fits together with tolerances less than a human hair. Visible are the breather holes in the bottom bracket shell. They will transfer argon gas through the frame providing an inert atmosphere for the welds. The oxygen-free environment keeps the welds clean and eliminates contamination when the weld wire is in a molten state.

Hoses outfitted with quick-disconnect fittings drape from the adjustable frame jig. The quick-connects are mated to Seven’s custom heat sink/argon couplers that work to reduce heat build-up in critical junctions while providing an outlet for the flow of argon. In Seven’s weld process, all the equipment is specially designed to handle the flow of argon and the prevention of contamination.

In the welder’s hands the torches, lenses and cups are paint brush and canvas. Seven is steadfastly committed to flawless welding.

Like the machining portion of the Seven build process, welding employs practices to maintain frame alignment. Each frame undergoes seventeen different alignment checks during welding. After all, a well-built frame must be straight to provide optimal handling characteristics and tracking. No one wants to experience a poorly aligned frame’s sketchiness at speed.

Part 2

Seven’s method of choice for joining thin-walled steel tubing is TIG (Tungsten Inert Gas) welding. Tungsten is used as a non-consumable electrode which produces the weld and at first glance the tungsten rod protruding from the tip of a welding gun looks much like the tip of a mechanical pencil; the big exception of course is it transfers enough electrical current to melt metals! We touched on the inert gas portion of the weld process in Part One.

One of Seven’s most notable features is the quality of their welds. TIG welding is an exceptionally neat, clean process and although it requires more patience then other methods in the hands of a skilled welder the results can be both suitable for the rigors of Aerospace applications and breathtaking to look at. Good quality TIG welding has a uniformed appearance, resembling a stack of dimes, each weld puddle consistent with the last and the spacing of each equal in distance throughout the length a the weld.

Properly executed welds bring together many variables that, when done properly insure optimal joint strength. Weld penetration, cleanliness, welder technique and heat are all aspects that must be in place for a weld to be strong and to go the distance. The shot below shows a welded steel frame fresh from the hands of a Seven welder. The discoloration or ‘bluing’ from the heat of weld process still visible.

The heat required to weld steel or titanium is extreme, well above 1700°C. With this much heat, a secondary consideration is created: distortion caused by the welding process. Seven takes steps to minimize the effects of heat including the use of heat sinks in critical weld junctions and by alternating weld sequences. Thin walled tubing has a tendency to pull or lift toward the heat source so Seven’s welders essentially focus on welding different parts of the frame as required to minimize distortion. Using the weld’s heat in an opposing direction will assist in pulling the tubing back into alignment reducing the amount of required post-weld alignment.

Throughout the welding of a Seven multiple weld wire diameters are used. Weld wire serves as a filler and consists of a like material such as titanium or steel. Various weld wires are paired with technique will insure proper weld penetration and the minimization of heat. A great example of this can be seen when comparing the weld bead at the bottom bracket shell/down tube junction and the seat stay bridge. In the photos above and below a titanium frame shows the variation in bead diameter from seat stay bridge to BB/down tube junction. Note the insane consistency in bead spacing. In the words of Milton Bradley: “it takes a very steady hand”…

From any angle, at any distance the quality of the Seven welds are without fault and are literally the traits that cycling lore is built. To weld frames at Seven, one must pass though Seven’s in house training which takes more than a year to complete. Like all endeavors requiring skill and determination, not everyone who enters Seven’s apprenticeship program makes it through to go on and weld at Seven. If your travels ever bring you to Watertown, Massachusetts drop in at Seven and ask to meet Tim D. Tim Delaney is the guy who brought the puddle bead weld to titanium frames and literally sits atop the pyramid of titanium frame welders. Tim’s the guy Seven owners can thank for all the oohs and ahhs that come from admirers of Seven’s welds.